Carol M. Hodgson ©

|

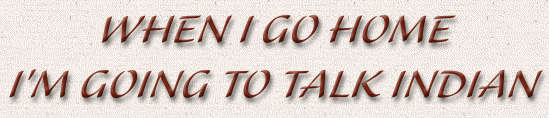

My best friend, Rose, was the most fun in the world. I looked forward each day to meeting her in the school hallway just before the bell rang. She often wore a barely-suppressed grin, or covered her mouth with her hand. I would spend recess trying to get her tell me what the joke was. Usually, she had managed undetected to plant a stone on Sister's chair or sneak an extra crust of bread from the supper hall. Rose, head bobbing, dark eyes twinkling, would finally share her secret transgression with me, causing us both to burst into uncontrollable giggles, and occasionally drawing the attention of a stony-faced nun who, disturbed by our laughter, would shoo us to move on. The Catholic Mission loomed at the far end of the only road cutting through Fort Providence, Northwest Territories. In l954, I entered my first year of school there as the only "white kid". My father spent his days predicting weather and tapping it in Morse Code, down to a military base in Hay River. My mother cooked, knitted, sewed my clothes and preserved berries. I, being a spirited 5 year old, knew that we lived in an exciting place, accessible only by barge or float plane and snowed under nine months of the year. The Mission school was the place for me to go to and hang out with other children.I didn't question the locked iron doors, the bars on the windows, the unreasonable rules imposed by the nuns. I didn't find it unusual that my playmates were several hundred native children who lived at the school rather than with their families. It was my only experience of school and I had no need to question. The day I arrived at school and didn't see Rose, I thought she must be ill. The recess bell finally rang and, in the impish manner I had learned from my friend, I quietly slid down the forbidding corridors that led to the dormitory. The nun who was changing the beds glared at me as though I wasn't meant to exist. I lowered my eyes to my shoes, knowing the necessary rules to avoid having to stand in the corner or get the strap.

I heard the squeak of her black boots, the jangle of her crucifix and the angry swish of her robes as she came closer.

I scurried back to the coatroom and pulled on my parka and touque. She must be outside, I thought, struggling to push open the heavy back door. Children filled the snowy yard, screaming, laughing, building snow forts and pulling each other around on little pieces of cardboard. It was freezing today and the nuns gathered close to the building, warming their hands over the fire barrel. I stood on the high stone steps, searching everywhere for Rose's red jacket. Finally I spotted her in the farthest corner, standing with her face to the fence, no friends around.

I shouted as loudly as I could, running down the steps and slogging through the deepest part of the snow where the other children had not gone. When I reached her, I tugged on her sleeve.

She kept her back to me, warming her hands under her jacket. Impatiently, I tugged again, sure that the bell would ring at any moment and we would have no time to play. Now she turned, her face drawn with pain and fury. She held up her red, swollen hands and I knew then that she hadn't been warming them, but holding, protecting them as best she could, from the searing pain. I saw the tears, which had frozen on her beautiful cheeks.

The bell rang and neither one of us moved. Cold needled into our faces and I stood,watching Rose breathe rapid frosty puffs into the bleak northern air. I didn't know what to do for my friend. When I looked back, I saw the other children were almost all inside.

She nodded, wiping her face in her sleeve. We couldn't hold hands like we usually did. Instead, I touched her shoulder as we walked toward the stone steps, where two nuns stood like sentries, waiting for us. Rose and I never talked about what had happened to her. We still sat together everyday and traded the ribbons in our hair. We built forts and pulled each other around in the snow on pieces of cardboard. Rose talked longingly of eating her granny's toasted bannock and romping in the woods with her younger sisters, who hadn't yet arrived at the Mission school. Our family left Fort Providence two years later. In the time I knew her, Rose never did get to go home. Copyright © Carol M. Hodgson, March 2000 All Rights Reserved

|

Return to Let all that is Indian within you die! The Reservation School system 1870-1928